The Film Noir Foundation's second annual Noir City Xmas was held December 14, 2011 at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, offering a double-feature of rare noir-stained yuletide classics "to darken our spirits this holiday season." The evening also featured the unveiling of the full schedule for Noir City X, the 10th anniversary of the world's most popular film noir festival, coming to the Castro Theatre January 20-29, 2012.

The Film Noir Foundation's second annual Noir City Xmas was held December 14, 2011 at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, offering a double-feature of rare noir-stained yuletide classics "to darken our spirits this holiday season." The evening also featured the unveiling of the full schedule for Noir City X, the 10th anniversary of the world's most popular film noir festival, coming to the Castro Theatre January 20-29, 2012.

Bill Arney—the now legendary disembodied "Voice of Film Noir"—hesitated to welcome the audience to the second "annual" Noir City Xmas because "just how many Noir City Xmas movies can there be?" Asking if the audience had been good this year, Arney was met with a resounding, "NO!" to which he responded, "What the hell is wrong with you? There's still a little over a week," he added "to get over yourself and make some trouble. Santa will be sorely disappointed if he doesn't get to fill every stocking in Noir City with coal this year. In some places this holiday is a winter wonderland, but here in Noir City it's just cold." Varney then introduced his boss, the "Czar of Noir" Eddie Muller: "The guy who only puts goodies in your cinematic stocking."

Muller took to the Castro stage and wished everyone a "cruel Yule." "You learn to expect the unexpected at Noir City," he offered. "Hence, a film noir double-bill starring Deanna Durbin. Here's the reality of film programming in 2011. As Bill said in his introduction, how many film noir Christmas movies can there be, right? So we have to parcel these out very intelligently. The plan originally was to show Christmas Holiday (1944) and Holiday Affair (1949) as our double-bill this year and next year we would have Lady On a Train (1945) and The Lady in the Lake (1947), which was set at Christmas, right? But, could we get Holiday Affair in a 35mm print? No. Because it no longer exists. This is a major problem. And that is why—when someone asked me earlier, 'What's the theme of this year's Noir City festival?'—I said, 'The theme is you better see it in 35mm while you can.' That is actually the theme of the festival and I'm very happy to say and proud to say that everything we will be screening at Noir City X will be in 35mm."

Muller took to the Castro stage and wished everyone a "cruel Yule." "You learn to expect the unexpected at Noir City," he offered. "Hence, a film noir double-bill starring Deanna Durbin. Here's the reality of film programming in 2011. As Bill said in his introduction, how many film noir Christmas movies can there be, right? So we have to parcel these out very intelligently. The plan originally was to show Christmas Holiday (1944) and Holiday Affair (1949) as our double-bill this year and next year we would have Lady On a Train (1945) and The Lady in the Lake (1947), which was set at Christmas, right? But, could we get Holiday Affair in a 35mm print? No. Because it no longer exists. This is a major problem. And that is why—when someone asked me earlier, 'What's the theme of this year's Noir City festival?'—I said, 'The theme is you better see it in 35mm while you can.' That is actually the theme of the festival and I'm very happy to say and proud to say that everything we will be screening at Noir City X will be in 35mm."

"I will not be on the soapbox tonight," Muller assured us, "but, I will be stationed on that soapbox during January because this has really become a serious issue. We cannot actually fight the tide forever—we are going to be living in a digital future—but, we have to do everything we possibly can to insure that films that do not exist digitally or on 35mm are preserved as films, or they will never be able to be shown in the future digitally or any other way."

Excited that his audience had been given a peek at the upcoming line-up for Noir City X, Muller emphasized he was especially excited because of his super special guest who would be appearing on the first Saturday night with The Killers (1964) and Point Blank (1967): Angie Dickinson! "I've already been warned to lay off the stuff about the White House and Jack Kennedy and all of that—I'm not going there—so I'll get it all out right now: they say she went in Police Girl and she came out Police Woman."

Excited that his audience had been given a peek at the upcoming line-up for Noir City X, Muller emphasized he was especially excited because of his super special guest who would be appearing on the first Saturday night with The Killers (1964) and Point Blank (1967): Angie Dickinson! "I've already been warned to lay off the stuff about the White House and Jack Kennedy and all of that—I'm not going there—so I'll get it all out right now: they say she went in Police Girl and she came out Police Woman."

Among the marvelous preservations that will be shown at Noir City X is a brand new print of Naked Alibi (1954) starring Gloria Grahame, struck by Universal specifically for Noir City. "All you need to know," Muller insisted, "is that it's called Naked Alibi." Further, in light of the upcoming Baz Luhrmann adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 classic The Great Gatsby (featuring Leonardo DiCaprio), Noir City has rescued from obscurity the 1949 film noir version of Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby starring Alan Ladd, which has not been shown theatrically since 1974 when it was put into deep storage to make way for the Robert Redford-Mia Farrow vehicle. Thanks to Noir City's good friends at Universal Studios, the 1949 version will finally be seen again. The Great Gatsby will be shown with Three Strangers (1946), whose preservation has been funded by the Film Noir Foundation. Finally, last but not least, The Film Noir Foundation vied with Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation to restore The Breaking Point (1950). Scorsese won that particular competition but Muller bears no regrets since it's one of his favorite films, one he has shown at other film noir festivals, thereby singlehandedly destroying the only existing good print left of the film. Muller is delighted that the film has been completely restored and that Scorsese and the Film Foundation have graciously allowed Noir City to be the first venue to show that brand-new print.

Among the marvelous preservations that will be shown at Noir City X is a brand new print of Naked Alibi (1954) starring Gloria Grahame, struck by Universal specifically for Noir City. "All you need to know," Muller insisted, "is that it's called Naked Alibi." Further, in light of the upcoming Baz Luhrmann adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 classic The Great Gatsby (featuring Leonardo DiCaprio), Noir City has rescued from obscurity the 1949 film noir version of Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby starring Alan Ladd, which has not been shown theatrically since 1974 when it was put into deep storage to make way for the Robert Redford-Mia Farrow vehicle. Thanks to Noir City's good friends at Universal Studios, the 1949 version will finally be seen again. The Great Gatsby will be shown with Three Strangers (1946), whose preservation has been funded by the Film Noir Foundation. Finally, last but not least, The Film Noir Foundation vied with Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation to restore The Breaking Point (1950). Scorsese won that particular competition but Muller bears no regrets since it's one of his favorite films, one he has shown at other film noir festivals, thereby singlehandedly destroying the only existing good print left of the film. Muller is delighted that the film has been completely restored and that Scorsese and the Film Foundation have graciously allowed Noir City to be the first venue to show that brand-new print.

To celebrate Noir City's 10th anniversary in style, on Saturday night, January 28, Noir City will be hosting its first-ever Noir City Nightclub called—appropriately enough—"Everyone Comes to Eddie's". Noir City is converting the Swedish American Hall into a sexy and sinister 1940s nightclub with live entertainment "for your edification."

Another highlight of Noir City X will be the all-day Dashiell Hammett marathon, featuring films based on Hammett's stories, including such rareties as Roadhouse Nights (1930) and Mister Dynamite (1935). Richard Laymann, the world's foremost scholar on Dashiell Hammett (Shadowman: The Life of Dashiell Hammett, 1981), will be flying in to Noir City because he has never seen Mister Dynamite, that's how rarely it's shown.

Another highlight of Noir City X will be the all-day Dashiell Hammett marathon, featuring films based on Hammett's stories, including such rareties as Roadhouse Nights (1930) and Mister Dynamite (1935). Richard Laymann, the world's foremost scholar on Dashiell Hammett (Shadowman: The Life of Dashiell Hammett, 1981), will be flying in to Noir City because he has never seen Mister Dynamite, that's how rarely it's shown.

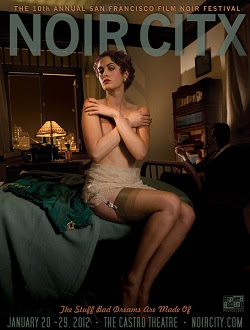

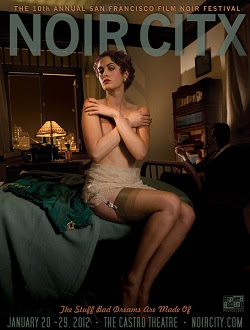

Finally, with regard to "the super sexy poster" for Noir City X, the photograph was actually taken in Dashiell Hammett's San Francisco apartment where he lived and wrote The Dain Curse (1929), Red Harvest (1929) and The Maltese Falcon (1930). Bill Arney, the "Voice of Noir City" resided in Hammett's apartment for many years and—looking at this poster—Muller had to ask Arney why he ever left? "Well," Arney responded, "the last one of those dames that came over there told me that the Murphy bed was very comfortable. I told her not to get too comfortable. And then I married her."

Turning to the evening's double-bill, Muller recalled that Deanna Durbin was once one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood and, as a girl, was credited with rescuing Universal Studios from bankruptcy in the 1930s when she became, by far, the most popular female performer in the United States. She had an outstanding singing voice and an amazing on-screen charisma and was everybody's favorite "girl next door" and the Great American Gal. But, of course, as she grew older, she chafed at being typecast in such roles. As she grew up into a woman, she wanted to stretch out and do other things.

In Lady on a Train, Nikki Collins (Durbin) witnesses a murder while waiting for a train, but can't get the police to believe her when no body is discovered. While they dismiss her as daft, she enlists the help of a mystery writer to sleuth out the culprits on her own. Based on a story by veteran mystery writer Leslie Charteris (The Saint), this is a wildly entertaining mix of comedy, musical, and suspense, rendered in evocative noir style by cameraman Woody Bredell (Phantom Lady, Christmas Holiday, The Killers), and featuring a superb cast of sinister and suspicious supporting players swirling ominously around "America's Sweetheart."

In Lady on a Train, Nikki Collins (Durbin) witnesses a murder while waiting for a train, but can't get the police to believe her when no body is discovered. While they dismiss her as daft, she enlists the help of a mystery writer to sleuth out the culprits on her own. Based on a story by veteran mystery writer Leslie Charteris (The Saint), this is a wildly entertaining mix of comedy, musical, and suspense, rendered in evocative noir style by cameraman Woody Bredell (Phantom Lady, Christmas Holiday, The Killers), and featuring a superb cast of sinister and suspicious supporting players swirling ominously around "America's Sweetheart."

Muller promised his audience that they would love Lady On A Train. "You'll laugh. You'll cry. You'll tap your feet to this charming film that is, unfortunately, not very well known." Lady On a Train was one of only two films directed by Charles Henri David who would—after this film—become Mr. Deanna Durbin. In 1948 when Durbin decided that her string had played out in Hollywood, she married David and smartly moved to France where, Muller was happy to say, she lives to this day, having recently turned 90 years old on December 4.

Watching Lady On a Train with me was my friend Mike Black who reminded me of an anecdote from Gore Vidal's memoir Palimpsest: "Deanna Durbin [was] a child soprano and competitor of Judy Garland, whose imitations of her rival were marvelously cruel, invoking a crooked arm and a radiant mad smile to match luminous crossed eyes. But Garland could be equally mordant about herself. When she had made her triumphant comeback at the Palladium in London, inspired by merry schadenfreude, she rang her now-forgotten rival. After many delays and false starts, Garland got the sleepy, ill-tempered Durbin at home in the French countryside. 'Tonight I had the greatest audience of my life!' At length, Judy recounted her triumph. Finally, out of breath, she stopped. There was a long silence. Then a pitying voice said: 'Are you still in that asshole business?' "

Watching Lady On a Train with me was my friend Mike Black who reminded me of an anecdote from Gore Vidal's memoir Palimpsest: "Deanna Durbin [was] a child soprano and competitor of Judy Garland, whose imitations of her rival were marvelously cruel, invoking a crooked arm and a radiant mad smile to match luminous crossed eyes. But Garland could be equally mordant about herself. When she had made her triumphant comeback at the Palladium in London, inspired by merry schadenfreude, she rang her now-forgotten rival. After many delays and false starts, Garland got the sleepy, ill-tempered Durbin at home in the French countryside. 'Tonight I had the greatest audience of my life!' At length, Judy recounted her triumph. Finally, out of breath, she stopped. There was a long silence. Then a pitying voice said: 'Are you still in that asshole business?' "

In Christmas Holiday, a young soldier gets more than he bargained for on a holiday stopover in New Orleans when he is introduced to a young "singer" (prostitute) and a local "nightclub" (brothel) and he learns the tale of her descent into degradation. Venerable scribe Herman Mankiewicz hews Somerset Maugham's novel into a brilliant script, directed with delirious intensity by Siodmak. Deanna Durbin is memorable in her first adult role, and Gene Kelly is unforgettable as the murderous cad with whom she tragically falls in love. Unquestionably the most romantically soul-crushing Christmas movie ever made.

In Christmas Holiday, a young soldier gets more than he bargained for on a holiday stopover in New Orleans when he is introduced to a young "singer" (prostitute) and a local "nightclub" (brothel) and he learns the tale of her descent into degradation. Venerable scribe Herman Mankiewicz hews Somerset Maugham's novel into a brilliant script, directed with delirious intensity by Siodmak. Deanna Durbin is memorable in her first adult role, and Gene Kelly is unforgettable as the murderous cad with whom she tragically falls in love. Unquestionably the most romantically soul-crushing Christmas movie ever made.

Muller considers Siodmak to be the greatest director of film noir there ever was and describes Christmas Holiday as a strange and mesmerizing film. "Why it's called Christmas Holiday, who the hell knows," Muller laughed but assured his audience that by the end of the film they would leave the Castro Theater thoroughly depressed. "That's our mission. Happy to fulfill it."

Muller considers Siodmak to be the greatest director of film noir there ever was and describes Christmas Holiday as a strange and mesmerizing film. "Why it's called Christmas Holiday, who the hell knows," Muller laughed but assured his audience that by the end of the film they would leave the Castro Theater thoroughly depressed. "That's our mission. Happy to fulfill it."

Muller dedicated the evening to Deanna Durbin, as well as to an old friend of his who passed away this year—one he recalls watching Christmas Holiday with in the Castro Theater—his great pal and mentor George Kuchar.

Of related interest: At Greenbriar Picture Shows, John McElwee responds to Noir City Xmas with a write-up on the Durbin films plus a lovely gallery.

As dreadful and terrifying as Dark Country (2009) became by film's end, Eddie Muller insisted this horror-noir thriller was his type of a fun movie. With director-actor Thomas Jane joining him on-stage at the Castro Theatre for the film's one-off theatrical screening on November 18, 2011, and with their conversation being filmed (in 3D) for inclusion in the deluxe DVD release, Muller wasted no time eliciting Jane's commentary on the making of the film and tracing Dark Country's inspirations. "Was it obvious," Muller asked, "when you were finally going to direct the film that it was going to be a film like this?"

As dreadful and terrifying as Dark Country (2009) became by film's end, Eddie Muller insisted this horror-noir thriller was his type of a fun movie. With director-actor Thomas Jane joining him on-stage at the Castro Theatre for the film's one-off theatrical screening on November 18, 2011, and with their conversation being filmed (in 3D) for inclusion in the deluxe DVD release, Muller wasted no time eliciting Jane's commentary on the making of the film and tracing Dark Country's inspirations. "Was it obvious," Muller asked, "when you were finally going to direct the film that it was going to be a film like this?"

Jane responded that—for his first-time directorial effort—he had been looking for a project small enough to contain, which even then turned out to have its own set of incredible problems. A huge film noir fan, Jane had grown up reading EC comic books and watching The Twilight Zone: all influences on Dark Country. The project kicked off when a good friend of his sent him a dark and twisted short story by Tab Murphy—known more for writing screenplays for Disney's animated films The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) and Tarzan (1999)—and Jane knew right off that it would make a good film. Since after doing The Punisher (2004) Jane had a deal with Lionsgate, they bought the idea for Dark Country for $3,000,000 and hired Murphy to draft a script. But when at their first production meeting Jane proposed to Lionsgate that the film should be shot in 3D, they balked and backed out. No one was doing 3D at that time. Jane's suggestion was at least a full year ahead of the 3D curve.

Jane responded that—for his first-time directorial effort—he had been looking for a project small enough to contain, which even then turned out to have its own set of incredible problems. A huge film noir fan, Jane had grown up reading EC comic books and watching The Twilight Zone: all influences on Dark Country. The project kicked off when a good friend of his sent him a dark and twisted short story by Tab Murphy—known more for writing screenplays for Disney's animated films The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) and Tarzan (1999)—and Jane knew right off that it would make a good film. Since after doing The Punisher (2004) Jane had a deal with Lionsgate, they bought the idea for Dark Country for $3,000,000 and hired Murphy to draft a script. But when at their first production meeting Jane proposed to Lionsgate that the film should be shot in 3D, they balked and backed out. No one was doing 3D at that time. Jane's suggestion was at least a full year ahead of the 3D curve.

But Jane was committed to the idea, having already met Ray "3D" Zone, who was known for his pioneering methods of converting flat images (in particular, comic books) into 3D images. Jane had grown up reading 3D comics like The Rocketeer and Twisted Tales that featured Zone's stereoscopic effects and so—when they met at a meeting of the Stereo Club of Southern California (SCSC), an organization formed in 1950—Jane took the opportunity to express his admiration of Zone's 3D comics and mentioned that he wanted to work with him. Jane joked that the SCSC gets together in a church basement once a month to show each other nudie pictures in 3D; but, the bottom line was that SCSC members are the leading experts in their craft. They encouraged Jane to consider making a film in 3D and were already creating work on their own jerryrigged 3D cameras back when people were first starting to make their own movies on the RED and DSLRs. It was at the SCSC meetings that Jane learned about how technological advancements were affecting the way 3D movies were being made and how the seeds of the 3D movement were being planted.

But Jane was committed to the idea, having already met Ray "3D" Zone, who was known for his pioneering methods of converting flat images (in particular, comic books) into 3D images. Jane had grown up reading 3D comics like The Rocketeer and Twisted Tales that featured Zone's stereoscopic effects and so—when they met at a meeting of the Stereo Club of Southern California (SCSC), an organization formed in 1950—Jane took the opportunity to express his admiration of Zone's 3D comics and mentioned that he wanted to work with him. Jane joked that the SCSC gets together in a church basement once a month to show each other nudie pictures in 3D; but, the bottom line was that SCSC members are the leading experts in their craft. They encouraged Jane to consider making a film in 3D and were already creating work on their own jerryrigged 3D cameras back when people were first starting to make their own movies on the RED and DSLRs. It was at the SCSC meetings that Jane learned about how technological advancements were affecting the way 3D movies were being made and how the seeds of the 3D movement were being planted.

Once Lionsgate backed away from the concept, wishing him good luck, Jane arranged for a meeting with Sony Home Video, who agreed to the project because they were hoping for homegrown content to support the 3D televisions they knew they would be placing in people's homes in the near future. Unfortunately there were no cameras to shoot a 3D film and no experienced 3D cinematographers so Jane hunted down Paradise FX who had done all the 3D effects for amusement park rides and convinced them to jump on board to engineer a 3D movie. They broke new ground. They rigged up huge cameras out in the desert with operators connected to cables, cables running all along the ground, and often the weather was so cold that the static electricity froze the cables up so that they couldn't shoot. A simple story with four characters that Jane thought would be a great way to "pop his cherry" as a director turned into a little bit more than he could chew.

Nonetheless, Jane persevered because he wanted the film to look like Edward Ulmer's Detour (1945), one of his favorite noirs. Paying homage to films from the '30s and the '40s, Jane utilized rear screen projections to create effects Muller described as "fabulous artificiality." Muller praised that Jane sought to create "a complete non-existent netherworld out there in the desert where anything can happen. How many claps of lightning can you have in one shot? I mean, it's fantastic." The film was shot quickly over two weeks and Jane pursued the feel of "hand-made set pieces" characteristic of noirs-made-on-the-cheap-and-dirty. When Jane cast Lauren German as Gina, he gave her a copy of Detour as homework for her part. Other direct influences on Dark Country besides Detour were Otto Preminger's Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), from which Jane cribbed. A few ideas were also lifted from David Lynch's Lost Highway (1997).

Nonetheless, Jane persevered because he wanted the film to look like Edward Ulmer's Detour (1945), one of his favorite noirs. Paying homage to films from the '30s and the '40s, Jane utilized rear screen projections to create effects Muller described as "fabulous artificiality." Muller praised that Jane sought to create "a complete non-existent netherworld out there in the desert where anything can happen. How many claps of lightning can you have in one shot? I mean, it's fantastic." The film was shot quickly over two weeks and Jane pursued the feel of "hand-made set pieces" characteristic of noirs-made-on-the-cheap-and-dirty. When Jane cast Lauren German as Gina, he gave her a copy of Detour as homework for her part. Other direct influences on Dark Country besides Detour were Otto Preminger's Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), from which Jane cribbed. A few ideas were also lifted from David Lynch's Lost Highway (1997).

Muller singled out the shot where Jane comes out of the diner and the camera circles 360° around his car at the gaspump. "I could almost feel Tom Neal and Ann Savage hitchhiking on the side of the road," Muller evoked. "I could almost feel the black and white creeping in." Jane had, in fact, tried to convince Sony to shoot the film in black and white—an idea that didn't go over well—even though he was convinced it would be "cool." Muller was wondering what gave Jane "the stones" to go into Sony and ask for 3D and B&W? Jane admitted: "I was just excited by the possibility of breaking new ground and doing something that hadn't been done before on a budget where no risk was involved."

Jane's ideal version of Dark Country would have been 79 minutes long and that was the way he planned it because it was the way he'd always wanted it. As a further homage to Detour (which Ulmer pared down to a concise 68 minutes), Jane wanted his film short. He fantasized that—with Eddie Muller doing commentary on his 79-minute film—it would become the noir of his dreams. But when Sony saw the film they gave him a note that the film needed to be at least five minutes longer. "Are you kidding me?" he thought. "This is a note from the studio? They want me to add something back in? Seriously?" Sony insisted because—in order for certain of their territories to buy and distribute the DVD—the film had to be 84 minutes long. That's why, Jane apologized, some of the scenes in the car are desultory and a bit talky. Originally, those scenes had fallen to the editing room floor on day one.

Jane's ideal version of Dark Country would have been 79 minutes long and that was the way he planned it because it was the way he'd always wanted it. As a further homage to Detour (which Ulmer pared down to a concise 68 minutes), Jane wanted his film short. He fantasized that—with Eddie Muller doing commentary on his 79-minute film—it would become the noir of his dreams. But when Sony saw the film they gave him a note that the film needed to be at least five minutes longer. "Are you kidding me?" he thought. "This is a note from the studio? They want me to add something back in? Seriously?" Sony insisted because—in order for certain of their territories to buy and distribute the DVD—the film had to be 84 minutes long. That's why, Jane apologized, some of the scenes in the car are desultory and a bit talky. Originally, those scenes had fallen to the editing room floor on day one.

How tough was it, Muller queried, to not only come up with all these technological advances and direct the film but to also perform in front of the camera? Overwhelmed, Jane phoned up Mel Gibson. "The first guy to go to for advice, right?" Muller quipped. Jane told Gibson he was making this little movie over at Sony that was going straight to video but that he was also directing it, as well as acting in it, and how would one go about that? Gibson sympathized, "Yup. Yup. My first film was this little film Man Without A Face (1993) and it occurred to me that I had never directed so I nervously phoned up Clint Eastwood." Eastwood told Gibson he had experienced the same problem. "Don't tell me Clint called up Kevin Costner?" Muller laughingly interjected. No, Jane rallied, Eastwood didn't call Kevin Costner; but, he did call his buddy Don Siegel who told Eastwood not to shortchange himself as an actor just because he was directing as well. He told him to treat himself like he treated any other actor. "The tendency would be to shoot yourself and get on with it," Siegel warned, "but don't do that. Take the time and do what you would do acting with anyone else. Watch playback and treat it like a job. Take it seriously." Gibson talked to Jane for over an hour, offered all kinds of advice, and after their conversation Jane felt he might be able to pull the film off after all.

How tough was it, Muller queried, to not only come up with all these technological advances and direct the film but to also perform in front of the camera? Overwhelmed, Jane phoned up Mel Gibson. "The first guy to go to for advice, right?" Muller quipped. Jane told Gibson he was making this little movie over at Sony that was going straight to video but that he was also directing it, as well as acting in it, and how would one go about that? Gibson sympathized, "Yup. Yup. My first film was this little film Man Without A Face (1993) and it occurred to me that I had never directed so I nervously phoned up Clint Eastwood." Eastwood told Gibson he had experienced the same problem. "Don't tell me Clint called up Kevin Costner?" Muller laughingly interjected. No, Jane rallied, Eastwood didn't call Kevin Costner; but, he did call his buddy Don Siegel who told Eastwood not to shortchange himself as an actor just because he was directing as well. He told him to treat himself like he treated any other actor. "The tendency would be to shoot yourself and get on with it," Siegel warned, "but don't do that. Take the time and do what you would do acting with anyone else. Watch playback and treat it like a job. Take it seriously." Gibson talked to Jane for over an hour, offered all kinds of advice, and after their conversation Jane felt he might be able to pull the film off after all.

To make sure, Jane strategized that it would help to have extra eyes around on set so he hired Ray Zone as his 3D consultant. [Zone speaks to the experience on his own website.] Jane had already overprepared for the film by storyboarding every shot of the movie with storyboard artist Dave Allcock. They used a little toy car to set up the shots, which was a lot of fun. ( Dave, incidentally, has a cameo in Dark Country. He and his girlfriend are on the missing poster.)

To make sure, Jane strategized that it would help to have extra eyes around on set so he hired Ray Zone as his 3D consultant. [Zone speaks to the experience on his own website.] Jane had already overprepared for the film by storyboarding every shot of the movie with storyboard artist Dave Allcock. They used a little toy car to set up the shots, which was a lot of fun. ( Dave, incidentally, has a cameo in Dark Country. He and his girlfriend are on the missing poster.)

Then Ray Zone and Jane sat down at Jane's kitchen table and worked on the storyboard Jane had developed with Allcock. They developed a fun, color-coded system where they used magic markers to color every storyboard frame with different colors to indicate where they wanted the 3D to sit. Blue was in the frame, red was outside the frame and yellow was somewhere in the middle. That was their method for constructing the 3D in such a way that there would be continuity to the shots and they wouldn't be jarring or out of focus. But most importantly, learning from and building upon the mistakes that were made with 3D in the 1950s, Jane challenged himself by questioning how 3D effects could be used as part of the storytelling rather than mere spectacle? In Dark Country Jane tried to harness 3D to create a psychological landscape within the interior of the car. Muller riffed: "It's interesting you cite Detour. All the times that I've introduced Detour at film noir festivals, I always say, 'This movie is so cheap. It's so simple. It goes to show you that all you need to make film noir is a man, a woman, and a locked hotel room. And so you now prove that all you need is a man, a woman and a car in the desert. That's it!"

Jane qualified it should be a sexy car, which led Muller to mention that he originally thought Jane had removed the rear view mirror from the window of the car and placed it on the dashboard as a way to get around issues with the 3D filming, but Jane advised him that, no, the 1960-1961 Dodge Phoenix came with the rear view mirror on the dashboard; but, the real challenge was that they had to find three cars: two for use on the road and one in the studio. Thus, the initial 360° shot of the car confirmed it was a major character in the film.

Jane qualified it should be a sexy car, which led Muller to mention that he originally thought Jane had removed the rear view mirror from the window of the car and placed it on the dashboard as a way to get around issues with the 3D filming, but Jane advised him that, no, the 1960-1961 Dodge Phoenix came with the rear view mirror on the dashboard; but, the real challenge was that they had to find three cars: two for use on the road and one in the studio. Thus, the initial 360° shot of the car confirmed it was a major character in the film.

Muller offered that Jane had created what had now become one of his favorite noir scenes of all time. "You have to love it when you and Gina are in the parking lot of the rest stop and she complains, 'We've run over a guy. I've seen you murder somebody. We buried the body in the desert. All on our wedding day. It's not supposed to be like this!"

When Muller added that Dark Country was like "a comic book come to life", Jane was visibly pleased and admitted he loved hearing that because that was exactly what he wanted to create. He wanted the film to have that alternate reality comic book look without aping other comic adaptations like Dick Tracy (1990) or Sin City (2005). Though so many great comic book artists go unsung, they've influenced such well-known directors as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, among others, who have recognized the great shots to be gleaned from these graphics. "I stole as much as I possibly could," Jane confessed.

Pointing out that most people probably didn't know that Jane owned Raw Studios and was publishing comic books, he wondered who some of the unsung heroes were who influenced Jane? Jane recalled that his Dad bought him an issue of Mad Magazine when he was eight years old "and that was it." From there he made the leap to EC Comics. In the town where he grew up in Maryland there was a bookstore called Barbarian Books that was, in effect, his "home away from home". He had to walk sideways to make his way through overstuffed aisles. That was where he found all his EC reprints and Gladstone stuff and really got into "the joy and the art of the illustrated story." He fell in love with "the great beautiful world" of illustrators: Johnny Craig, Bernie Krigstein, Wally Wood, Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, among so many others. Jane's concern is keeping this culture alive for upcoming generations. He fears we're losing this "great beautiful world" to video games but believes there's still room for inspiring people and "doing work that lives in your brain and affects the way you see the world." When he got turned on to Berni Wrightson, for example, he saw the whole world through Bernie's eyes for months. He would see a girl and wonder how Bernie would draw the seams and creases in her skirt or the veins in her hands.

Pointing out that most people probably didn't know that Jane owned Raw Studios and was publishing comic books, he wondered who some of the unsung heroes were who influenced Jane? Jane recalled that his Dad bought him an issue of Mad Magazine when he was eight years old "and that was it." From there he made the leap to EC Comics. In the town where he grew up in Maryland there was a bookstore called Barbarian Books that was, in effect, his "home away from home". He had to walk sideways to make his way through overstuffed aisles. That was where he found all his EC reprints and Gladstone stuff and really got into "the joy and the art of the illustrated story." He fell in love with "the great beautiful world" of illustrators: Johnny Craig, Bernie Krigstein, Wally Wood, Frank Frazetta, Al Williamson, among so many others. Jane's concern is keeping this culture alive for upcoming generations. He fears we're losing this "great beautiful world" to video games but believes there's still room for inspiring people and "doing work that lives in your brain and affects the way you see the world." When he got turned on to Berni Wrightson, for example, he saw the whole world through Bernie's eyes for months. He would see a girl and wonder how Bernie would draw the seams and creases in her skirt or the veins in her hands.

The greatest influence on the film, however, was Thomas Ott's graphic novels, from which Jane admittedly lifted specific shots. Ott draws black and white stories without dialogue and his work resembles woodcuts or etchings. His framing in a story called Dead End in particular—which includes a long sequence of a guy driving through the desert—was a direct influence on Dark Country. To bring it full circle, Thomas Ott saw Dark Country and really liked it and—without knowing he was the inspiration—mentioned to Jane that he saw a lot of his own work in the movie. Jane asked him what he would think of doing a graphic novel adaptation of the film? Ott agreed to the suggestion, which Jane will put out through Raw Studios. On a recent trip to London Jane got together with Ott to take a look at the first pages and the experience was way too cool for him: he had envisioned Dark Country as a Thomas Ott novel and was now seeing it come to life through Ott's pen.

The greatest influence on the film, however, was Thomas Ott's graphic novels, from which Jane admittedly lifted specific shots. Ott draws black and white stories without dialogue and his work resembles woodcuts or etchings. His framing in a story called Dead End in particular—which includes a long sequence of a guy driving through the desert—was a direct influence on Dark Country. To bring it full circle, Thomas Ott saw Dark Country and really liked it and—without knowing he was the inspiration—mentioned to Jane that he saw a lot of his own work in the movie. Jane asked him what he would think of doing a graphic novel adaptation of the film? Ott agreed to the suggestion, which Jane will put out through Raw Studios. On a recent trip to London Jane got together with Ott to take a look at the first pages and the experience was way too cool for him: he had envisioned Dark Country as a Thomas Ott novel and was now seeing it come to life through Ott's pen.

Before he discovered acting, Jane had drawn a lot in high school. He had wanted to be an illustrator but decided he'd get laid a lot more if he acted. Though he was good, he didn't have the necessary discipline, that "thing" that allows an illustrator to zone in and get lost in the work, which is what separates the men from the boys: that ability to "sit down, roll up your sleeves, and knock it out." Because he didn't have that, he knew he would never really be a great artist. Jane mollifed himself by considering he might paint when he becomes an old man.

Muller then invited Ray Zone to the stage and explained that Ray was responsible for setting the Castro screening of Dark Country into motion. Ray had attended some of the Noir City screenings in Los Angeles, met Muller, and they had talked about Inferno (1953) and I, the Jury (1953), early film noirs that experimented with 3D. Then Zone asked Muller if he had seen Jane's 3D neo-noir Dark Country? They came up with the idea of screening Dark Country at the Castro and filming the on-stage conversation in 3D as a DVD extra and—as if to prove the point—Zone arrived on stage with paddle balls so that he, Jane and Muller could bounce paddle balls at the 3D camera set up off stage. Of course this was in homage to another 3D movie from 1953, Andre de Toth's House of Wax, wherein a paddleball man offered one of the best examples of the 3D experience at the time. Andre de Toth didn't want to include the scene, felt it distracted from the main narrative, but was forced to include it by Jack Warner and other studio execs. Some consider House of Wax the best 3D movie of all time, Muller reminded, even though it was made by a filmmaker with one eye who had no depth perception whatsoever.

Muller then invited Ray Zone to the stage and explained that Ray was responsible for setting the Castro screening of Dark Country into motion. Ray had attended some of the Noir City screenings in Los Angeles, met Muller, and they had talked about Inferno (1953) and I, the Jury (1953), early film noirs that experimented with 3D. Then Zone asked Muller if he had seen Jane's 3D neo-noir Dark Country? They came up with the idea of screening Dark Country at the Castro and filming the on-stage conversation in 3D as a DVD extra and—as if to prove the point—Zone arrived on stage with paddle balls so that he, Jane and Muller could bounce paddle balls at the 3D camera set up off stage. Of course this was in homage to another 3D movie from 1953, Andre de Toth's House of Wax, wherein a paddleball man offered one of the best examples of the 3D experience at the time. Andre de Toth didn't want to include the scene, felt it distracted from the main narrative, but was forced to include it by Jack Warner and other studio execs. Some consider House of Wax the best 3D movie of all time, Muller reminded, even though it was made by a filmmaker with one eye who had no depth perception whatsoever.

Jane quoted John Ford as saying that it's the mistakes that are often the most interesting parts of a movie. Ron Perlman's line about leaving "no turn unstoned" was an adlib. Ron—sloughing 90 pounds of make-up—had flown directly to New Mexico from the set of Hellboy 2 to shoot Dark Country.

Although Dark Country was set on a hot summer night in the desert, in reality they were shooting in November in New Mexico and it was "butt ugly cold." The ground was frozen rock hard. The actors had to use tricks like sucking on ice cubes before delivering lines so that their breath wouldn't vaporize. (Sucking on ice cubes gives an actor about 30 seconds where their breath doesn't show in cold air.) Hearing this made Muller appreciate the scene where Lauren German hangs her head out the window and moans, "It's soooooo hot." Jane recalled that German wore a tiny shift as thin as tissue paper during those cold night shoots. She was the smallest, thinnest person on the crew and was freezing. They had to to give her vitamin shots and fly her home to Los Angeles on the weekends to warm her up.

As for whether Jane would take on directing another 3D film? Absolutely. In the spirit of John Wayne's 3D western Hondo (1953), Jane would like to film a 3D gothic western, perhaps even a noir western. Ray Zone brought up that Raoul Walsh, another great noir director, also directed westerns that had dark tones. Wrapping up, Jane said that screening Dark Country in 3D on the Castro Theater's large screen was the pinnacle of his whole experience of making the film because it was the way the film was meant to be seen, by an audience who "got" it. He never thought the day would come. "I literally built this film for this audience in this theater," he beamed.

Muller admitted that hosting the Dark Country event was a crossroads for him in his career as the "Czar of Noir" because the entire event was digital. Earlier in the day, he had a conversation with a friend in the Castro about the future of 35mm film projection and how difficult it's becoming to get the studios to continue shipping 35mm prints. Three major studios—Warner Brothers, Paramount and Fox—are completely shutting down shipment of 35mm prints. Within the year, these studios will no longer allow Noir City to show their slate in 35mm. Noir City X (January 20-29, 2012) might possibly be the Film Noir Foundation's final 35mm-exclusive festival. It might certainly be the last time some of the films on the Noir City X program will be shown to the public in 35mm. "There's nothing anyone can do to stop this," Muller sighed. "The future is happening right now."

Muller admitted that hosting the Dark Country event was a crossroads for him in his career as the "Czar of Noir" because the entire event was digital. Earlier in the day, he had a conversation with a friend in the Castro about the future of 35mm film projection and how difficult it's becoming to get the studios to continue shipping 35mm prints. Three major studios—Warner Brothers, Paramount and Fox—are completely shutting down shipment of 35mm prints. Within the year, these studios will no longer allow Noir City to show their slate in 35mm. Noir City X (January 20-29, 2012) might possibly be the Film Noir Foundation's final 35mm-exclusive festival. It might certainly be the last time some of the films on the Noir City X program will be shown to the public in 35mm. "There's nothing anyone can do to stop this," Muller sighed. "The future is happening right now."

Muller qualified that—as long as they preserve a film somehow on film—then he can live with the changes to come. They can digitize the prints and make film trafficking wonderful and easy and all that but he insists they mustn't lose the film in the process while converting inventory over to new digital formats. There are certain titles that are becoming extinct because they are being ignored in the rush to digital. It's well-known that film remains the best medium for preserving film and that digital copies are too volatile, requiring migration from one form of storage to the next as hardware and storage systems change.

I caught Tatiana Huezo's remarkable documentary The Tiniest Place (El lugar mas pequeño, 2011) at the 54th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF) and had the welcome opportunity to sit down to speak with her. The timing couldn't have been worse, however, for transcribing our conversation as I was in the middle of relocating from California to Idaho where—almost immediately—I was caught up tending to family emergencies. Several months later, I guiltily agonized over missing my initial window of opportunity; but, now, with The Tiniest Place continuing to gather accolades on its festival trajectory, and with its arrival at the 23rd edition of the Palm Springs International Film Festival in their True Stories sidebar, I welcomed the chance to revisit our conversation.

I caught Tatiana Huezo's remarkable documentary The Tiniest Place (El lugar mas pequeño, 2011) at the 54th edition of the San Francisco International Film Festival (SFIFF) and had the welcome opportunity to sit down to speak with her. The timing couldn't have been worse, however, for transcribing our conversation as I was in the middle of relocating from California to Idaho where—almost immediately—I was caught up tending to family emergencies. Several months later, I guiltily agonized over missing my initial window of opportunity; but, now, with The Tiniest Place continuing to gather accolades on its festival trajectory, and with its arrival at the 23rd edition of the Palm Springs International Film Festival in their True Stories sidebar, I welcomed the chance to revisit our conversation.

Born in 1972 in El Salvador, Tatiana Huezo moved to Mexico City at age five. A graduate of the prestigious Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (CCC), she's the recipient of the Gucci / Ambulante award, a grant established in 2007 to support new and established Mexican documentarians. Huezo has taught documentary films at the University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. The Tiniest Place is her first feature-length documentary. Winner of awards at numerous festivals, including Visions du Reel (Best Feature Film), Documenta Madrid (Audience Award), Lima International (Best Documentary), Monterrey International (Best Mexican Film), DOCSDF (Best Mexican Documentary, Best Cinematography), Abu Dhabi (Jury's Special Award), and DOK Leipzig (Best Documentary), The Tiniest Place continues to astound audiences with its message of perseverance and hope.

Born in 1972 in El Salvador, Tatiana Huezo moved to Mexico City at age five. A graduate of the prestigious Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (CCC), she's the recipient of the Gucci / Ambulante award, a grant established in 2007 to support new and established Mexican documentarians. Huezo has taught documentary films at the University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. The Tiniest Place is her first feature-length documentary. Winner of awards at numerous festivals, including Visions du Reel (Best Feature Film), Documenta Madrid (Audience Award), Lima International (Best Documentary), Monterrey International (Best Mexican Film), DOCSDF (Best Mexican Documentary, Best Cinematography), Abu Dhabi (Jury's Special Award), and DOK Leipzig (Best Documentary), The Tiniest Place continues to astound audiences with its message of perseverance and hope.

At Variety, Robert Koehler has championed the film, naming Huezo "one of the bright new talents of Latin American cinema" and proclaiming that the "film's beauty would be more than enough to recommend it, but Huezo's work, supported by Ernesto Pardo's incandescent cinematography, is more than simply gorgeous. It manages a highly unusual synthesis of personal human stories . . . ."

At Variety, Robert Koehler has championed the film, naming Huezo "one of the bright new talents of Latin American cinema" and proclaiming that the "film's beauty would be more than enough to recommend it, but Huezo's work, supported by Ernesto Pardo's incandescent cinematography, is more than simply gorgeous. It manages a highly unusual synthesis of personal human stories . . . ."

At The Hollywood Reporter, Sheri Linden describes the film as "impressionistic and precise" and "a beautifully rendered memory piece that insists on the necessity of memory" honoring the "will to live and the way unquenchable grief informs . . . joy."

Huezo follows in a longstanding Latin American tradition of equating the diminutive—the "tiniest"—with that which is most intimate and human and (ultimately) the best in mankind. My thanks to SFIFF publicist Julieta Esteban for setting up the interview and to Claudia Prado of the Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica for her translative assistance.

* * *

Michael Guillén: Tatiana, tell me about your educational background and how you came to work with the Centro to produce The Tiniest Place?

Michael Guillén: Tatiana, tell me about your educational background and how you came to work with the Centro to produce The Tiniest Place?

Tatiana Huezo: I studied at the Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica (CCC) where I specialized in cinematography and film direction. After that, I pursued a Masters degree in documentary production at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain.

Guillén: By any chance, when you were studying in Spain did you meet José Luis Guerín?

Huezo: Yes, he was my professor. I only had two classes with him but I admire his work immensely. He has had a profound influence on my own work.

Guillén: Having spoken with several Mexican filmmakers, it strikes me that a current trend in Mexican filmmaking is to have collectives of artisans working together. Are you involved in a similar collective at the Centro?

Huezo: I'm not working within a Mexican collective, no, partly because I have been away from Mexico for a while living in Madrid for several years pursuing my studies; but, I'll be returning to Mexico soon.

Guillén: One of my continuing interests is in the evolving nature of national cinemas and whether or not that is a category that can be effectively used anymore. You're Mexican, studying in Spain, and producing a documentary about El Salvador. How, then, would you define yourself within the context of a national cinema?

Huezo: I define myself more as a Mexican because I grew up in Mexico and that's where I received most of my education—it's my culture and it is the spirit informing my work and what I do—but my origin is Salvadorian, that remains inside me, and that's what gave origin to this particular project. I left Mexico to continue my studies because there was no place in Mexico for me to go for post-graduate studies in documentary filmmaking. In fact, there are no post-graduate programs for filmmaking in Mexico, which is why I went to Barcelona to pursue my Masters. Despite the fact that the core of my education was in Mexico—and I had marvelous teachers!—what determined my true documentary training was the education I received in Barcelona. It was the encounter between these two cultures—my Latin American roots and the European vision—that was important in my formation as a filmmaker. It was important for me to encounter and see these different ways of telling stories.

Guillén: Fascinating. It confirms for me my sense that many young filmmakers are coming out of these cross-cultural encounters. In my estimation, this is true world cinema that is neither defined nor delimited by national cinema(s). You're a classic case.

Guillén: Fascinating. It confirms for me my sense that many young filmmakers are coming out of these cross-cultural encounters. In my estimation, this is true world cinema that is neither defined nor delimited by national cinema(s). You're a classic case.

At the Q&A after your screening at the Pacific Film Archive the other night, I was intrigued by your story about how—once your arrived at Cinquera, El Salvador, your grandmother's birthplace—a woman approached you, thinking you were someone else who had disappeared during the war. Can you speak to what you felt from that experience?

Huezo: It was a disconcerting moment because it was my first time to visit Cinquera and my first walk through the village by myself. There are only four to five streets in Cinquera and I was walking near the town plaza. I was looking around with profound curiosity because there were traces of the war everywhere, in every part of the town, on the walls, on the street, and suddenly while I was walking down one of these streets an old woman threw herself at me, hugged me and wouldn't let me go. She kept saying, "You haven't changed. You haven't changed." I felt ashamed because I wasn't the person she thought I was. I felt like I couldn't live up to her expectations. In that moment, I wanted to be the person she thought I was and to be able to hug her back with the same intensity and affirm, "Yes, I am that person." But, instead, I had to tell her that she was making a mistake and that I wasn't that person . She insisted, "But, yes, you are! You are her! You came back!"

Guillén: A bit scary, but sad?

Huezo: Yes, it was both scary and sad. Right now, speaking to you about this, I'm also remembering an image of an older woman sitting inside a house that had no roof but that had bars across the door. She was just sitting there combing her hair. It was a surreal image because it was just these four walls, the door with bars, and no roof. I think this old woman was not quite right in the head and I suspect her son had left her locked up there so he could go out to work.

Huezo: Yes, it was both scary and sad. Right now, speaking to you about this, I'm also remembering an image of an older woman sitting inside a house that had no roof but that had bars across the door. She was just sitting there combing her hair. It was a surreal image because it was just these four walls, the door with bars, and no roof. I think this old woman was not quite right in the head and I suspect her son had left her locked up there so he could go out to work.

On one of the days after we were done shooting, we saw an old man walking with a cane who kept hitting the pavement with his cane as if he were still fighting, cursing out loud against the army that had invaded Cinquera. It's clear to me that there are many people who lost their minds during the war, especially the older people. Don Pablo Alvarenga, who is in my film, told me that when the people get to a certain age, when they're really old, it seems like they disconnect from reality and return to the time of the war. They spend their last years in a delirium of the war.

I don't want to place the woman who hugged me so intensely in exactly the same category as these older mentally-troubled people, but she did have a bit of that quality in the way she recognized in my face the face of another from that time.

Guillén: Which reminds me of the important statement made in your film that these survivors are living in two worlds at once. Let alone your assertion that you made this film about war because you have never experienced war. What is it you hope audiences will take away from this film?

Huezo: It was Don Pablo who made that statement that the survivors of Cinquera are living in two worlds at once and Don Pablo is a poet. Describing how the survivors experience the past and the present at once is his poetry. He is always able to make images out of his words to communicate what he is going through. When Don Pablo said that to me, I knew this would stay in the film and that, in fact, it was the exact metaphor that this film needed because this is an experience shared by all of the people in that town. The people of Cinquera live among ghosts. This is their reality.

Huezo: It was Don Pablo who made that statement that the survivors of Cinquera are living in two worlds at once and Don Pablo is a poet. Describing how the survivors experience the past and the present at once is his poetry. He is always able to make images out of his words to communicate what he is going through. When Don Pablo said that to me, I knew this would stay in the film and that, in fact, it was the exact metaphor that this film needed because this is an experience shared by all of the people in that town. The people of Cinquera live among ghosts. This is their reality.

Guillén: It spoke to me. As someone who lived in San Francisco through the AIDS pandemic in the '80s when I lost so many friends and loved ones, I can attest to living in a comparable state where the past and the present are irrefutably fused. I survived and currently live a healthy life; but, I constantly walk among ghosts in a zone where the living and the dead are caught in the grip of a death horizon.

Your film's strength lies in its respect for Don Pablo's poetic insight, expressed—interestingly enough—in the film's structure, which replicates this notion of two worlds existing at the same time through the relationship between your visuals and your voiceovers.

Huezo: You're right. There are those two structural elements of the visual and the oral; but, I hadn't thought of them in the way you're expressing them.

Guillén: Yet this is how it seems to me. You've caught your subjects in moments of visual repose where they're either quiet, thoughtful, even happy, but the voiceovers speak to a more horrible world of witnessed atrocities. You've structured the film so that they're both going on at the same time.

Huezo: I knew when we made the film that there would be these two discourses—the oral and the visual—and that they would be independent of each other; but, I also knew that by putting them together it would create a third discourse.

Guillén: That third discourse is the film's healing property; the documentary's remedy, if you will. As someone who lives, as I mentioned before, in two worlds caught in the grip of the death horizon, it's exactly by living in that way that I am able to honor the past and keep living. I honor the past by carrying it with me at all times.

Huezo: I have to be honest and say that all of this process was somewhat unconscious for me when I was making the film and something of an experiment; but, what I learned the most from making the film was how people learn to live with their pain. This has to do with those two elements combining into a third discourse which you've called healing. Healing is not about forgetting or about stopping suffering over what has happened. Healing is about learning to live with it.

Guillén: Or what my mentor Joseph Campbell once termed: "Joyfully participating in the sorrows of the world." Another intriguing theme in your film, both subtle and controversial, is that—normally in such beleaguered situations as this—people would turn to religion; but, I got the sense in your film that established religion had been replaced by the religiosity of personal memories, which is to say spiritual insight.

Huezo: Religion was, in fact, the origin of the uprising of these people and at the core of their rebellion. Many of the priests who arrived in this town practiced liberation theology. They helped open the people's eyes.

Guillén: Ah. I'm familiar with liberation theology as practiced among indigenous people in Central America, specifically Guatemala, and its role in populist uprisings against oppressive forces. Ironically enough, one of those oppressive forces was the authoritative hierarchy of the Catholic Church itself so it's always been a bit of a conundrum for me to associate liberation theology with the Catholic Church, even though it is without question one of its most important ministries, albeit controversial. Controversial, precisely, for opening eyes.

Huezo: Once a week the townspeople meet on Thursday nights and Pablo reads to them from a Latin American Bible; one I've never seen before. They cling to every word that was taught to them by the priests who practiced liberation theology. They read fragments of this Bible and try to relate its message to the lives they are living. They translate those fragments to the injustices of the present and to their needs in the present. Their minds are strong!

Huezo: Once a week the townspeople meet on Thursday nights and Pablo reads to them from a Latin American Bible; one I've never seen before. They cling to every word that was taught to them by the priests who practiced liberation theology. They read fragments of this Bible and try to relate its message to the lives they are living. They translate those fragments to the injustices of the present and to their needs in the present. Their minds are strong!

Guillén: Which explains why liberation theology and its teachings among the marginalized people of El Salvador proved such a threat to the military.

Huezo: Totally.

Guillén: Along with Pablo's voiceover, the voice of Elba Escalante, the woman who had lost her daughter, was simply amazing, which leads me to ask how you gained the trust of the five main voices used in your film? How did you single them out from the town's inhabitants? Why were they willing to tell you their intimate stories?

Huezo: Pablo is a friend of my grandmother's. He's something of a grandfather to me as well. Elba—who is nicknamed "La Sirena" (The Mermaid)—is the mother who had lost her daughter and I first saw her at the same time the audience first sees her: lying there on her side. After the trip I took to Cinquera with my grandmother, I returned and lived there for two months and it was during that time that I encountered and got to know the personalities who became a part of my film. In my first encounter with Elba, she started telling me stories about how her daughter was killed. It was almost as if I were someone who lived in Cinquera and she was just filling me in about what had happened since last we met.

Huezo: Pablo is a friend of my grandmother's. He's something of a grandfather to me as well. Elba—who is nicknamed "La Sirena" (The Mermaid)—is the mother who had lost her daughter and I first saw her at the same time the audience first sees her: lying there on her side. After the trip I took to Cinquera with my grandmother, I returned and lived there for two months and it was during that time that I encountered and got to know the personalities who became a part of my film. In my first encounter with Elba, she started telling me stories about how her daughter was killed. It was almost as if I were someone who lived in Cinquera and she was just filling me in about what had happened since last we met.

Guillén: Elba is an amazing personality. She radiates life in the way she takes care of her plants and broods over her chicken eggs. Despite what had happened to her—perhaps because of what had happened to her?—life pours out of her.

Huezo: Elba is incredible. She's a woman who lives with much passion, full of life, but when she talks about her daughter it's like she breaks in half, transforms, and becomes dark. These two extreme sides of her, all of her light and all of her darkness, quickly made her one of the main "characters" of the movie.

Huezo: Elba is incredible. She's a woman who lives with much passion, full of life, but when she talks about her daughter it's like she breaks in half, transforms, and becomes dark. These two extreme sides of her, all of her light and all of her darkness, quickly made her one of the main "characters" of the movie.

Guillén: It stands to follow that those who are caught in the grip of the death horizon are often the best storytellers.

Huezo: Definitely, yes.

Guillén: Let's talk a bit about your immaculate sound design, right down to the final cock's crow in the closing credits, which somehow makes the audience feel good or hopeful as they're getting up to leave the theater. My main complaint about investigative documentaries is that they often take you to the heart of difficult issues without either offering remedy or guiding you back out. Something about that cock's crow brought us back out of the film into our everyday lives.

Huezo: For me it was important to tell the story of Cinquera as if it were a fairy tale that had monsters. Not only was it important for me to capture the dignity of these people but I wanted to close the story with that because this town in the end was not trapped in darkness. They continued to work their land and to take care of their animals. They continued to educate their children. This is their light.

Huezo: For me it was important to tell the story of Cinquera as if it were a fairy tale that had monsters. Not only was it important for me to capture the dignity of these people but I wanted to close the story with that because this town in the end was not trapped in darkness. They continued to work their land and to take care of their animals. They continued to educate their children. This is their light.

Guillén: I respect that you portrayed that dignity in alignment with nature.

Huezo: They have a special connection and consciousness and love of the land, which accounts for why they returned to lift Cinquera from the ashes. Pablo, for example, has a garden and he has tried very hard to keep out transgenic seeds. The people of Cinquera have transmitted to me their love for this forest. For me, indeed, the forest is one of the film's characters.

Guillén: The voice of that forest truly emerged in your sound design: the bird trills, the little ditty about the frogs, all of that is a voice I'm familiar with having worked in Central American rainforest for many years.

Huezo: I collaborated on the sound with my excellent sound designer Lena Esquenazi and my direct sound recorder Federico Gonzalez. Federico understood that we had to capture every available sound in the forest; in other words, the soul of the forest in sounds. So he went out at different times of the day to capture different atmospheres: the sounds of the morning, the sounds in the afternoon, the sounds at night. We ended up with recordings of all the sounds of the forest at different hours of the day and night available to us. I'm proud of the direct sounds in the movie, which I think are very good. It was a challenge for Federico because he recorded it all on his own; he didn't have an assistant. He had all his equipment and two microphones, was carrying everything himself, walking miles and miles and miles. It was very hard for him. He was a warrior! Afterwards, I sought out a woman I deeply admire—Lena Esquenazi—who I felt was one of the best sound designers existing in Mexico. She lived in Mexico but now she lives in Buenos Aires. We worked on the sound design together for two months.

Huezo: I collaborated on the sound with my excellent sound designer Lena Esquenazi and my direct sound recorder Federico Gonzalez. Federico understood that we had to capture every available sound in the forest; in other words, the soul of the forest in sounds. So he went out at different times of the day to capture different atmospheres: the sounds of the morning, the sounds in the afternoon, the sounds at night. We ended up with recordings of all the sounds of the forest at different hours of the day and night available to us. I'm proud of the direct sounds in the movie, which I think are very good. It was a challenge for Federico because he recorded it all on his own; he didn't have an assistant. He had all his equipment and two microphones, was carrying everything himself, walking miles and miles and miles. It was very hard for him. He was a warrior! Afterwards, I sought out a woman I deeply admire—Lena Esquenazi—who I felt was one of the best sound designers existing in Mexico. She lived in Mexico but now she lives in Buenos Aires. We worked on the sound design together for two months.

Guillén: Can we speak about editing? To return to the idea of how you circled us out of the film's central trauma to provide hope or to allow us to experience the hope felt by the survivors of Cinquera, you achieved this through scenes that revealed their hope in increments: the scene of Elba and the eggs hatching, for example, and the scene of the cow giving birth. Where I really felt the horror of the war wash away was in the scene with the rainfall. Can you speak to how you placed those moments in the film to reveal this sense of hope? To create that feeling of relief and acceptance?

Huezo: Even before shooting the film, I had an idea of the film's structure. This structure was a very simple structure but it was what guided the shooting of the film. I wanted to tell the structure of the story as if it had happened over three days. Maybe that wasn't so clear to the audience that three days have passed, but in my mind that is how I structured it. In the first day I wanted to show the tranquil everyday life of the characters with very small brush strokes of what had happened in the past.

The second day was the war; a total immersion in the past. The first sequences of this second day were of the people who were young at the time of the war and who are my age now. I asked them to tell me their memories of being children during the war. From their childhood stories, this was how I opened the door to their past.

I knew that the cave was the heart of the movie and that the scene in the cave would be placed at the end of the second day. The cave was like going down to Hell; the moment of pain and loss. For me, the cave is a symbol above and beyond what happened there. I knew that the cave would be the meeting point for all of their stories and that's why I filmed that sequence where everyone was sitting in the cave telling their stories.

I knew that the cave was the heart of the movie and that the scene in the cave would be placed at the end of the second day. The cave was like going down to Hell; the moment of pain and loss. For me, the cave is a symbol above and beyond what happened there. I knew that the cave would be the meeting point for all of their stories and that's why I filmed that sequence where everyone was sitting in the cave telling their stories.

The third day was their going back to their everyday life. As a spectator, I was hoping we could reveal another dimension to that everyday life. If we had skipped over the second day and only shown the first and third days, the truth of their experience would not have had an impact. I was confident that the spectator would give a different value to the everyday actions shown on this third day after knowing who they were and what they suffered. After having spent time with them in the cave.

As for the pregnant cow, that was sheer luck. [Laughs.] To have the birth of this calf in the third day of this narrative structure was perfect for dramatic effect. And as for Elba, I had seen her nurturing the eggs on my first visit to Cinquera and—when I returned to shoot the film—I asked her to repeat the activity. I knew I was going to have chickens being hatched on the third day of the story but I didn't know I was going to have the calf being born.

Guillén: If I may say so, this three-day structure is religiously brilliant. Along with the obvious Christian parallel, there is the mythic undertone of the harrowing of Hell found in various world mythologies. Three days is the numerological template for resurrection. The Latin root for the word "religion" is religio whose meaning is influenced by the verb religare, which refers to that string that connects and binds the material to the immaterial, the obligation of soul to spirit. So when you're talking about having this thread that runs through the three days, I consider this a marvelous stroke of brilliance. Congratulations!

Guillén: If I may say so, this three-day structure is religiously brilliant. Along with the obvious Christian parallel, there is the mythic undertone of the harrowing of Hell found in various world mythologies. Three days is the numerological template for resurrection. The Latin root for the word "religion" is religio whose meaning is influenced by the verb religare, which refers to that string that connects and binds the material to the immaterial, the obligation of soul to spirit. So when you're talking about having this thread that runs through the three days, I consider this a marvelous stroke of brilliance. Congratulations!

Huezo: Thank you.

Guillén: So what's next for you?

Huezo: I have an idea for a story about how one makes a child one's own, even if they are not a biological child; but, I don't like to use the word adoption. Still, it's that idea. There will be two parallel stories. One is of a woman in search of a child for adoption and the other is of someone who has been happily adopted and is now older and going out to search for his biological mother. It's a story about identity and, in a way, it's about loss as well.

The Film Noir Foundation's second annual Noir City Xmas was held December 14, 2011 at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, offering a double-feature of rare noir-stained yuletide classics "to darken our spirits this holiday season." The evening also featured the unveiling of the full schedule for Noir City X, the 10th anniversary of the world's most popular film noir festival, coming to the Castro Theatre January 20-29, 2012.

The Film Noir Foundation's second annual Noir City Xmas was held December 14, 2011 at San Francisco's historic Castro Theatre, offering a double-feature of rare noir-stained yuletide classics "to darken our spirits this holiday season." The evening also featured the unveiling of the full schedule for Noir City X, the 10th anniversary of the world's most popular film noir festival, coming to the Castro Theatre January 20-29, 2012. Muller took to the Castro stage and wished everyone a "cruel Yule." "You learn to expect the unexpected at Noir City," he offered. "Hence, a film noir double-bill starring Deanna Durbin. Here's the reality of film programming in 2011. As Bill said in his introduction, how many film noir Christmas movies can there be, right? So we have to parcel these out very intelligently. The plan originally was to show Christmas Holiday (1944) and Holiday Affair (1949) as our double-bill this year and next year we would have Lady On a Train (1945) and The Lady in the Lake (1947), which was set at Christmas, right? But, could we get Holiday Affair in a 35mm print? No. Because it no longer exists. This is a major problem. And that is why—when someone asked me earlier, 'What's the theme of this year's Noir City festival?'—I said, 'The theme is you better see it in 35mm while you can.' That is actually the theme of the festival and I'm very happy to say and proud to say that everything we will be screening at Noir City X will be in 35mm."

Muller took to the Castro stage and wished everyone a "cruel Yule." "You learn to expect the unexpected at Noir City," he offered. "Hence, a film noir double-bill starring Deanna Durbin. Here's the reality of film programming in 2011. As Bill said in his introduction, how many film noir Christmas movies can there be, right? So we have to parcel these out very intelligently. The plan originally was to show Christmas Holiday (1944) and Holiday Affair (1949) as our double-bill this year and next year we would have Lady On a Train (1945) and The Lady in the Lake (1947), which was set at Christmas, right? But, could we get Holiday Affair in a 35mm print? No. Because it no longer exists. This is a major problem. And that is why—when someone asked me earlier, 'What's the theme of this year's Noir City festival?'—I said, 'The theme is you better see it in 35mm while you can.' That is actually the theme of the festival and I'm very happy to say and proud to say that everything we will be screening at Noir City X will be in 35mm." Excited that his audience had been given a peek at the upcoming line-up for Noir City X, Muller emphasized he was especially excited because of his super special guest who would be appearing on the first Saturday night with The Killers (1964) and Point Blank (1967): Angie Dickinson! "I've already been warned to lay off the stuff about the White House and Jack Kennedy and all of that—I'm not going there—so I'll get it all out right now: they say she went in Police Girl and she came out Police Woman."